While researching the recently certified world land wind speed record, I came across this excellent article, published in the University of Montana's Kaimin student paper, about the second edition of what is a really good book that I first read not too long after it's initial release.

While researching the recently certified world land wind speed record, I came across this excellent article, published in the University of Montana's Kaimin student paper, about the second edition of what is a really good book that I first read not too long after it's initial release.

Loving history novels, biographies, weather, and stories of adventure -even ones that end in disaster- "Not Without Peril: 150 Years of Misadventure on the Presidential Range of New Hampshire" puts it all together for me.

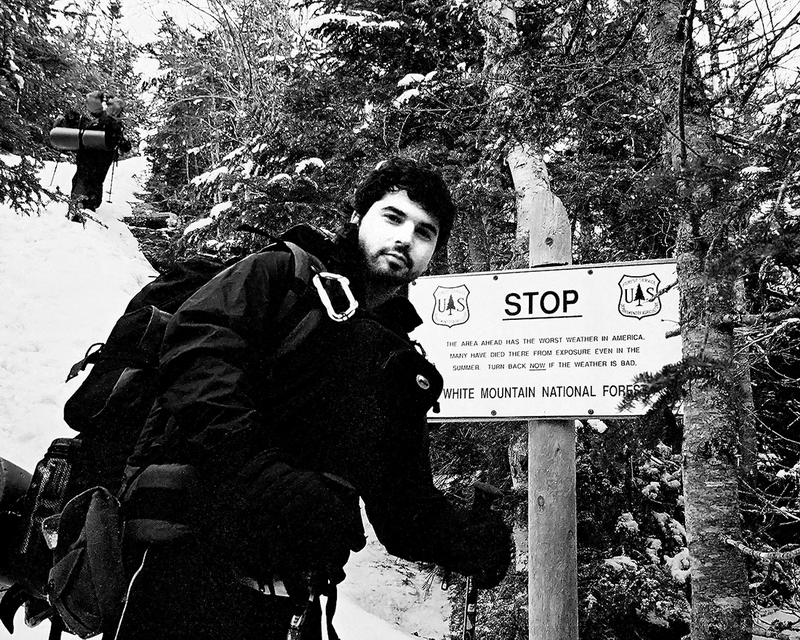

Although this is not a book specifically about mountaineering, like most good adventure novels, "Not Without Peril" is filled with simple mistakes that mean the stark difference between life and death in the mountains. Of course, even though the Presidential Range and it's surrounding peaks are not "high mountains", the weather and conditions are fierce, they offer technical ascent options, and as this book illustrates; are big enough to get you killed.

by Justin Franz | January 27, 2010 | Montana Kaimin

You would think the experience of being a teenager and carrying a dead man down a mountain, pushing on his lifeless skin to see that “it does not rebound, it does not press back,” would deter anyone from returning to such a place.

But Nicholas Howe has returned to Mount Washington time and time again, accepting the fact that death is simply part of life in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. He tells this tale in his book, “Not Without Peril: 150 Years of Misadventure on the Presidential Range of New Hampshire.”

Originally published in 2000, the book has been reprinted by Appalachian Mountain Club Books for its 10-year anniversary. Its return is no surprise, because the Boston Globe called the original one of the 100 essential books about New England, due to Howe’s second-to-none research of events going back to the first ascent of the mountain in 1638.

But you don’t have to be a native New Englander or history buff to be engulfed by Howe’s story of mistakes and “misadventures” on the tallest peak in the East.

Topping out at 6,288 feet, Mount Washington may seem like an anthill, even compared to the peaks around Missoula. But what makes it deadly is the weather.

Due to its location — at the convergence of multiple weather patterns from the Gulf, South Atlantic and Northwest — this mountain is known for its constantly changing weather. The fact that the mountain serves as a roadblock to weather patterns going through the region probably doesn’t help. All of this combines to set many records, including one of the highest surface winds ever recorded at 231 miles per hour.

With such environmental extremes, it is no wonder why National Geographic magazine called it “the killer next door.”

The mountain lives up to its fatal reputation: There were 140 known deaths occurring on the mountain between 1849 and 2008.

Most of the notable deaths are covered in Howe’s almost 300-page book that serves as both historic record and adventure novel. These include tragic events, such as when a father and his two daughters were marooned on an exposed ledge for an entire night, resulting in the death of one of the children (by dawn, they belatedly realized they were in sight of shelter).

But the most trying and startling story is that of the death of MacDonald Barr in August 1986. Hiking with his son and a German exchange student, the three were marooned atop Mount Madison, one of the lesser-known summits in the White Mountains. Running for help, the exchange student came upon an Appalachian Mountain Club shelter and crew, who sprang into action to do everything they could to save the two boys. But they had to make the decision of life or death for Barr, questioning if it was worth risking the lives of the rescue crew to save another.

With a hut full of hikers, the four-person crew had nowhere else to go to discuss the matter except a women’s bathroom. Cooped up in a small bathroom stall, they made the decision that would determine if a man would die.

“Even in the best circumstances imaginable, even on a walking path in the valley with fair skies and sweet breezes, the four members of the Madison crew would have difficulty managing a half-mile litter carry by themselves,” Howe wrote. “In the cold and dark and rain and rocks and wind, they would have no chance at all …. All of these thoughts were in the women’s bathroom, and even though not all of them were said out loud, the hut crew knew that they’d decided.”

But even with these sobering stories of death and pain, Howe doesn’t lessen the attraction of the White Mountains. Their beauty remains strong in the mind of the reader, but they must be respected and not underestimated. It’s that message of respect for the elements and mountains that stays with the reader long after the final page.

“Not Without Peril: 150 Years of Misadventure on the Presidential Range of New Hampshire” is $18.95 and can be ordered directly from the Appalachian Mountain Club at http://www.outdoors.org.

Original Article: Revised book depicts natural ‘killer’

So how bad is this book that I have relinquished it to a pulpy level? Actually, Nina Webb did an

So how bad is this book that I have relinquished it to a pulpy level? Actually, Nina Webb did an  It goes without saying, if not for Verplanck Colvin, I would have far less to blog about, far less to

It goes without saying, if not for Verplanck Colvin, I would have far less to blog about, far less to